WRITER | RYLEE WHITFORD

The Lost Art of Efficiency

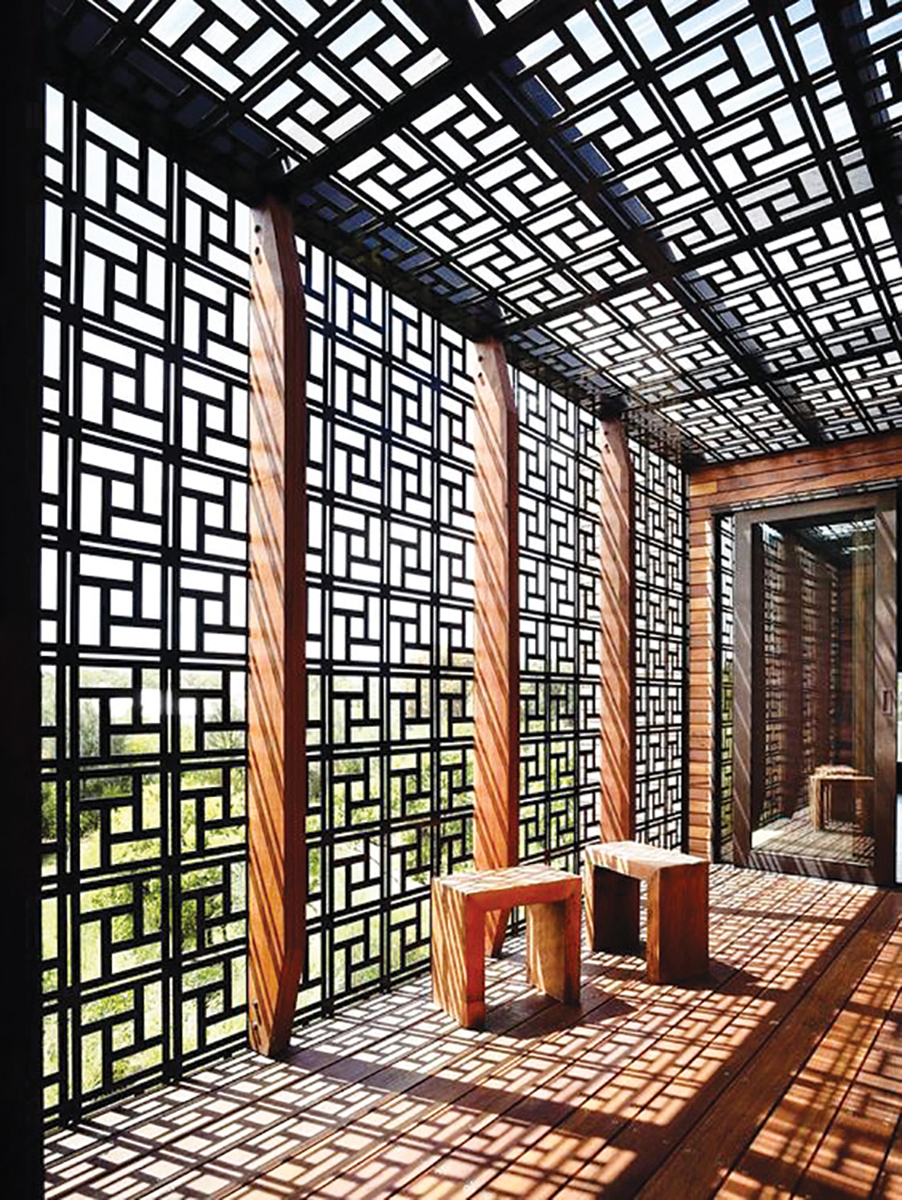

Chances are you’ve seen jaali but never knew it by name. It has been a common architectural detail in Hindu temples and Islamic buildings since the 14th century. Jaali translates as “net” and refers to perforated surfaces or latticed screens, typically with an ornamental geometric pattern. Along with being aesthetically pleasing, jaali has other benefits, making it the ideal solution for a hot and overcrowded Indian city – and potentially for your own home right here in Michigan as well!

When these perforated patterns first made their appearance across India in the 1300s, the designs were strictly geometrically influenced. During the Mughal Empire (1526-1707), when construction of the Taj Mahal was commissioned, the jaali adornment changed to stone carvings of plants and other natural elements. Historically, jaali was fashioned of carved stone, but these days other mediums are common, such as wood, cement, metal, or fiber-reinforced plastic. And although the patterns appear to be the most impressive part, you’ll be amazed at jaali’s functionality.

The first purpose of jaali is privacy; this is the biggest reason it became wildly popular in Indian culture and temple architecture. The cutout design allows those inside a building to see out but obstructs the view from the outside in, almost like a one-way mirror. Because of the light difference, our eyes can see the brightly lit outside, but those outside have a hard time adjusting to see a darker scene inside the structure. Along with acting as a built-in privacy curtain, the patterns can reduce the amount of sunlight and glare inside a room without affecting the overall illumination.

That said, perhaps the greatest benefit of jaali in a warm climate is that it intensifies air movement. You see, according to the Bernoulli and Venturi principles, when air passes through a small aperture, its velocity increases. In layman’s terms, when there is a slight breeze outside, air passes through the jaali holes, speeds up, and creates an even stronger breeze inside. This effect is controlled by how big the jaali holes are made. In hot and humid areas, they would use large holes to increase airflow and make the jaali less opaque; in drier, cooler climates, smaller holes would be more beneficial.

Although India’s jaali architecture largely met its match once British-inspired architecture proliferated during the last century and neighborhoods became more tightly packed, it seems a great loss. Not only was jaali a huge development in times long before electricity was harnessed, but it can still be applicable today.

Now is the perfect time to investigate simple, pragmatic solutions as we strive to be more energy-efficient and kinder to our environment. As part of your own “go green” movement, consider where jaali could be implemented in place of an air conditioner or a dehumidifier. Where might you use jaali on your next project? A screened porch? A greenhouse? A kitchen, even, or simply as a decorative element? The possibilities are endless!