WRITER | JULIE FORD

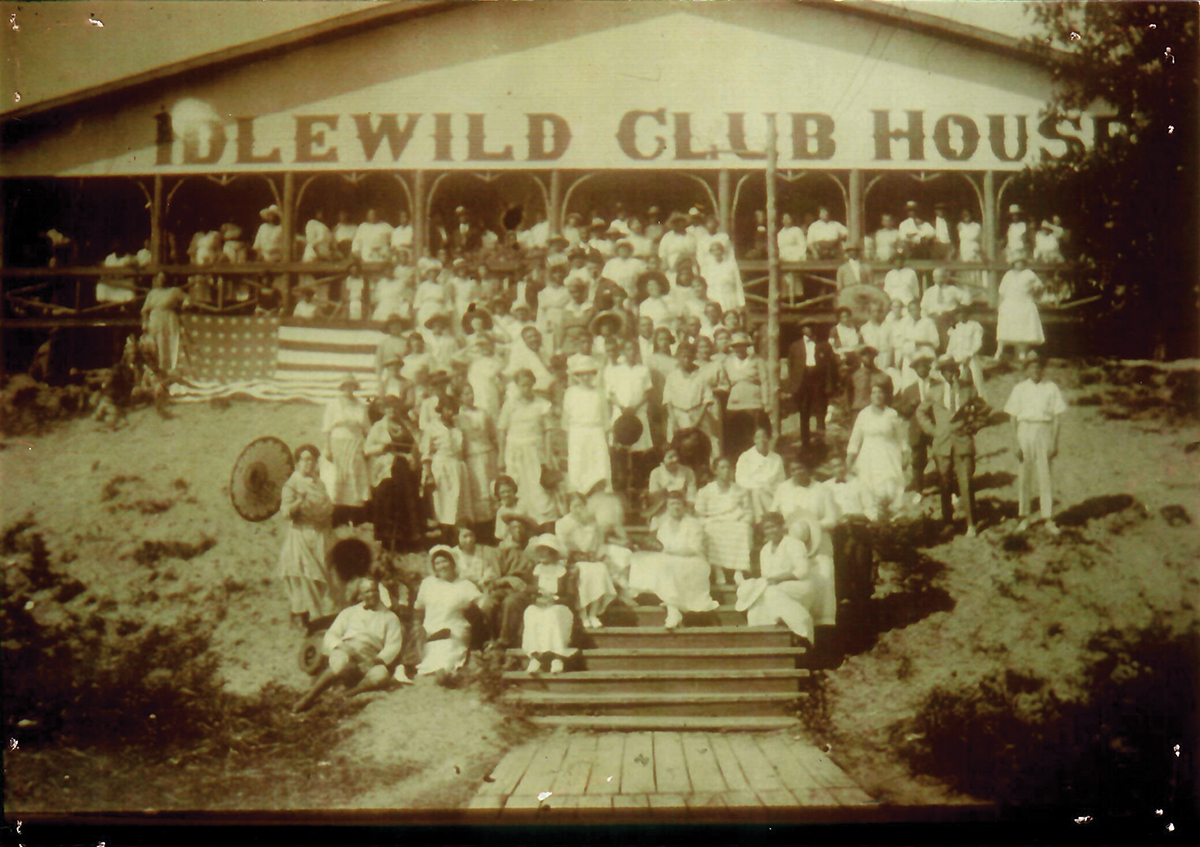

PHOTO | BEN C. WILSON COLLECTION, CARLEAN T. GILL

Rebuilding Paradise

Michigan’s resorts are cherished for their sandy beaches, warm summer breezes, and timeless ambiance. When they first appeared along the Lake Michigan shoreline in the 1800s, tourists reached the fashionable vacation destinations by train and steamboat; however, there was a period when Michigan’s resort communities weren’t accessible to everyone.

Between the 1870s and 1960s, the Jim Crow laws mandated a “separate but equal” status for African-Americans, and African-American tourists were not allowed at most resorts in Michigan for nearly 100 years. The combination of oppression and a business deal laid the foundation for Idlewild, the most popular black resort in the Midwest from 1912 to 1964. Also known as “Black Eden,” this was where professional and middle-class African-Americans could purchase property and find respite from racism to enjoy boating, swimming, fishing, hunting, horseback riding, roller skating, and Las Vegas-style shows featuring the top performers of the time.

Located 37 miles east of Ludington and just south of US 10, Idlewild was created on land where virgin pine forests were cleared to provide lumber for housing west of the Mississippi. In 1912, land speculators and brothers Adelbert and Erastus Branch purchased the land through tax sales, and along with developers Dr. Wilbur Lemon and Alvin Wright created the Idlewild Resort Company in 1925.

“The Branch brothers were speculators – hoping to make a profit later,” says Dr. Ben C. Wilson, professor emeritus of Africana Studies at Western Michigan University and co-author of Black Eden, The Idlewild Community. “They thought maybe they’d use the land and abundant inland lakes for hunting resorts and jumped on the idea as they witnessed the large migration north of southern blacks – refugees of oppression and the heinous, systemic racism of the South.”

Why would four white guys build a resort specifically to attract African-Americans in the early 1900s, when most of Michigan’s counties had Ku Klux Klan chapters? Wilson says it was because they were trying to make the fastest buck possible. And they did. Wilson’s fact-finding revealed that Lemon and a group of investors greatly profited by the time they sold their shares to the Idlewild Lot Owners Association in the late 1920s.

Through his extensive research, Wilson believes that Lemon’s networking finesse was critical to the success of Idlewild. Busloads of potential lot purchasers arrived in Idlewild from Grand Rapids, Detroit, Chicago, Indianapolis, and Cleveland. In its heyday of the 1940s to 1960s, more than 20,000 people visited Idlewild in the summer in addition to the pensioners who lived there year-round.

“My dad used to drive my great aunt and uncle, Robert and Margaret Riffe, back and forth from Cleveland to Idlewild – they owned the house that we grew up in,” says Gezelle Myers who, with her siblings and mother, still owns the family home. “My dad loved the woods and was tired of the city. When my aunt and uncle decided to sell, my parents bought their house.”

Myers, who lives in Midland, also owns a cottage just one-quarter mile from the family home. “We grew up on Idlewild Lake with a lot of visitors from out of town, same as back in the day. Some would stay the whole summer or come and go,” recalls Myers.

Idlewild is a National Register Historic District encompassing 2,536 acres and several lakes, including Idlewild Lake and Paradise Lake, and is located in the Manistee National Forest. Before World War II, many businesses developed at Idlewild to serve the increasing summer population. Hotels, motels, boarding houses, several nightclubs, grocery stores, and clothing stores sprung up quickly in the business district to fill the demand. After WWII, in the era of jazz-urban blues, greats like Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Etta James, and Lionel Hampton were just a few of a long list of popular performers who played Idlewild on what was known as the “chit’lin circuit.” The circuit provided a series of “safe” nightclubs for black performers in major US cities, mostly east of the Mississippi, during Jim Crowism.

Carlean Gill was one of 12 Fiesta Dolls, beautiful young ladies who performed Las Vegas-style shows with famous entertainers in the Fiesta Room at the Paradise Club owned by Arthur Braggs. Known for his exceptional promotion skills, Braggs was also the producer of the internationally renowned Arthur Braggs Idlewild Revue.

“I had a background in modeling and interviewed with Mr. Braggs,” says Gill, who grew up in Ferndale and graduated from Lincoln High School in the 1950s. “The Arthur Braggs Idlewild Revue came to a Detroit nightclub, and one of the girls was leaving the show and had to go back home.” Gill got the job and performed with the Revue, traveling the US, Canada, and Mexico in the 1960s and early 1970s.

“It was fantastic!” says Gill of her time in Idlewild, where the Revue was based. “The atmosphere was like a family – you could talk to anybody or go to anybody’s house, and a lot of the entertainers were just getting their hits.” Gill says Braggs was instrumental in bringing throngs of people to Idlewild because the Revue was seen in venues like the Apollo Theatre in New York City, and for his skill in producing high-end shows with the best talent.

“People would see this fabulous show and ask, ‘Where is Arthur Braggs Idlewild Revue?’ and that’s what would draw the people in (to Idlewild),” explains Gill. “After Labor Day, we’d start packing, go home for one week, and use the Green Book to travel by car to meet in New York City.”

The Green Book was similar to a AAA guide published for African-American tourists traveling during Jim Crowism. It was a guide for hotels, bed and breakfasts, tourist homes, service stations, taverns, nightclubs, car dealers, tailors, and any other services that might be needed while on the road. “You’d call people and tell them you are coming in; the band people stayed at one house and we would find another,” says Gill.

Idlewild was a beloved destination for six decades, but soon after Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964, African-American tourists could visit any resort area by law. White vacationers felt they were not welcome because they were not black, so Idlewild began losing its following.

Today, Idlewild is on a path of renewal, with two chambers of commerce, the Idlewild Community Development Corporation, and committees working together to bring visitors, businesses, and new residents to the area. There is plenty of optimism, a strategic plan, and many upcoming summer events to not only honor the rich history of Idlewild but also continue educating new generations about its significant part in Michigan’s history.

Idlewild Summer Events

May 17-19 Blessing of the Bikes

May 25 Paint the Lake Dinner Party

June 8 Jazzmin House Bike Ride & Tailgate

July 6 Mid-MI Music Event

July 6 Idlewild 4th of July Parade

July 17-21 Troutarama

July 26-28 ROI Music Retreat

August 2-4 Outdoor Afro Michigan Camping

August 3 Idlewild 7th Annual Homecoming

Jazz & Blues Festival

For up-to-date information on events, visit the Idlewild African American Chamber of Commerce.

IAACC.com